|

|

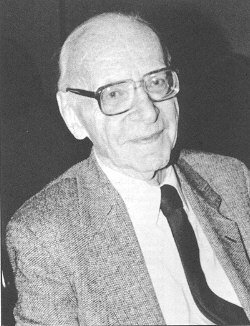

(Biographical excerpts from from the N.Y. Times obituary by Ford Burkhart, May 31, 1997.) Kurt Adler, the only son of Alfred Adler, was born in 1905 in Vienna, Austria. He received a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Vienna in 1935 and an M.D. from the Long Island College of Medicine in New York in 1941. He became a psychiatrist with the U.S. Army in World War II, and after the war began a private practice which he continued until a week before his death on May 28th, 1997. He was medical director and lecturer at the Alfred Adler Institute in New York City for 45 years and practiced at Lenox Hill Hospital. Extending his father's ideas, Kurt Adler said in his writings and speeches that mental health is achieved through integration into a community, when the person merges his or her own self-interest with the common interest of humanity.

(Our thanks to Horst Groner, editor of the Individual Psychology Newsletter, for permission to publish this interview from the Vol. 40, No. 2, April 1995 issue of the IPNL. Originally published in German, then translated and slightly edited by the Alfred Adler Institute of San Francisco, the material is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed consent of Mr. Groner and the AAISF.)

(Beginning of Interview) How did you, Kurt Adler, as a child, experience your father? As a father, he was always a friend. He was interested in everyone, always friendly. Most of the time. Sometimes he was also angry with people. Angry, when? When someone recommended to him something that seemed inappropriate, ways to distinguish himself financially. My father's office, when he practiced internal medicine in Vienna, was integrated into our apartment. I remember that when someone suggested that he locate a separate office, he came out of his office to us and said: "Well, I threw that guy out!" And your mother? How was she? Full of understanding. She did not have much of a sense of humor, in contrast to my father. She also lacked the gift for music. For example, she could not sing a melody. As children we made fun of her for that. Music seemed to have played an important role in your parents' home. Yes, above all for my father, but for me and my younger brother as well. My father played the piano and sang. I also sang. After my voice changed, I was a member of the Vienna Philharmonic Chorus. We enjoyed singing the songs of Robert Schumann, Franz Schubert, and Karl Loewe. My sister, Alexandra, also played four-handed piano with my father. Like many intellectuals at that time, your mother, the Russian Raissa Timofeyevna, was an idealistic socialist. She must have been a very courageous woman. Before the Russian Revolution, she was said to have smuggled several translated works of Karl Marx from Switzerland to Moscow. She possibly had no idea how dangerous that was. Under the Czar women were not even allowed to study. For that reason your mother studied biology and zoology for 22 years in Zurich. That must have been quite unusual, as well as expensive. She must have come from a well-to-do family. My grandfather's family, on my mother's side, owned much property and had extensive land holdings outside of Moscow, whole villages. I also remember wheat fields that were so large that they reached beyond the horizon, fragrant fruit orchards, and endless forests with wolves.

And what about a spacious manor house with staff? There were two houses; one main and a guest house. When we visited with my mother in the summer of 1914 we stayed in the smaller house in the park. We ate in the main building. You remained longer than was planned. During your stay World War I broke out. Yes, for six months we were unable to return to Vienna. I missed school, but I learned other things instead. What did you learn? You must have been nine years old at that time. I studied the cartoons of Emperor Franz Joseph and William II in the Russian newspapers. When I returned home, I studied the cartoons of the Russian Czar, King George V, and of French President Raymond Poincare in the Vienna newspapers. Did this then influence your views on nationalism in your childhood? Naturally. I also had hoped during that time that Germany and the Danube Monarchies would lose the war. This did not make it very easy for me in school. How were you able to return to Vienna from Moscow during the war? My mother had to call on the Czar to request that she be allowed to return with her children to the enemy country. She had to swear that she was forced to marry my father. Finally, in December, we were allowed to leave. We returned to Austria via Finland, Sweden and Germany. At your mother's side, your father turned into a humanistic socialist, so wrote his contemporary, Manes Sperber. The first fruit of that association was the socio-medical paper "Health Handbook for The Tailoring Trade" published in 1989. Even before he met my mother, my father had worked with the Socialist students, and had written numerous articles for the "Arbeiterzeitung," the organ of the Social Democrats. In your biography you described an atmosphere of equality that abided throughout your family home. Each child was respected as an individual with his and her own personality. There was no punishment. A nanny was fired because she raised a hand against one of your siblings. Was this not an unusual way of raising children at that time? Yes, very much so. One example: I attended a public school, Pädagogium, which was supported by the aristocrats. One day an archduchess came to visit the school. Since my name began with an A, I was the second student, after a girl, to greet the great lady. I saw how the girl curtsied. Since I had not learned how to bow, I imitated what the girl did and also curtsied. How old were you then? Perhaps six years of age. Contrary to your father, who started out in school poor in arithmetic but then made a breakthrough, you were always good in mathematics. I was considered a mathematical genius. At the age of three I was said to have asked: "Is five and eight thirteen?" The adults were surprised and asked: "How do you know that?" Later I studied physics and mathematics. After the immigration of our family to the United States, I also studied medicine and became a psychiatrist. What did your father read? It is said that he was well read in the works of Marx and Engels. Oh, yes. In his later theories, Manes Sperber rediscovered the dialectical starting points of the early socialists. I had given a report on that subject at the International Congress for Individual Psychology in 1993 in Budapest, because I wanted to encourage the Hungarians not to give up their socialist ideals completely. At the moment, however, history worldwide seems to run in the opposite direction. Yes, but the baby should not be thrown out with the bath water. What were your father's philosophical and ideological sources from which he drew? He was also said to have studied the stoics. Of course, but he also recognized the works of modern philosophers, particularly those of Hans Vaihinger. And also the writings of Jan Christian Smuts, who believed in a similar holistic approach, like your father, and also employed such concepts as "private logic" and "common sense." Yes, he had found Jan Smuts very interesting. What was your family's attitude toward Judaism? It is known that your parents both had a Jewish background, but were not what one would regard as "conscientious" Jews. (Laughing) No! How did your father see himself? As a citizen of the world? Yes, particularly in Vienna. In New York more than anywhere else, it is common to be with Jews. It was not until we lived in New York that we were confronted by that. Why did your father convert to Christianity? As a person who had socialist ideals, it would seem that he would have been an atheist. Yes, we are all atheists. Although Edward Hoffman, in his new biography about my father, called me an agnostic, with which I don't agree. He probably did not want to leave me as an atheist. Why then did your father convert? Probably because of the children. It was not allowed in those days to be "nothing." We had to participate in religion classes. Austria was up to 95% Catholic. We, however, converted to Protestantism. I attended Protestant religion classes along with three other boys. Only after the revolution in Austria was it allowed to leave the Church, which is what my father and I had done. Manes Sperber wrote that your father in his later years had yielded to a large extent to faith and metaphysics. My father did not change. However, he attributed increasing significance to the creative forces in human beings. Did this not in any way have something to do with a higher power? No, he was impressed by the spiritual powers in human beings. That also applies to me. Until this day, your father is often regarded as a pupil of Sigmund Freud. Individual Psychologists, as a rule, correct this and maintain that your father was not Freud's pupil, but had only participated in the Wednesday evening discussions that Sigmund Freud led. Nevertheless, between 1902 and until they broke up in 1908 he must have played a significant role in your father's life. Did you know Freud personally? No, I have never seen him. He was supposed to have been an unpleasant person, this Freud, very unsocial! Unlike my father, he never visited the coffee houses. Was the break-up between Alfred Adler and Sigmund Freud discussed in your home? No. Only later, when I was already an adult. The difference between the classical psychology of Freud and Individual Psychology is that classical psychoanalysis makes a determination about a person on the basis of his instincts and drives. Individual Psychology, on the other hand, perceives the person as an individual who, based on background, genetics, physical make-up, environment and experience, assumes a goal-directed life style. What is important is not from where that person came, but to where he directs himself. That is often being forgotten even by Individual Psychologists. This, however, becomes most important in order to understand and to treat a person. In those early years, my father was very impressed by Freud's ideas on the unconscious. Although he denied the use of that word as a noun, he did explore people's unconscious motives. He was also very impressed by Freud's dream analyses, even though he did not find them correct. It was the first time that anyone attributed any meaning to dreams. Freud also presented this as most exciting. Yes, he was an excellent writer. He should have been given the Nobel Prize for literature. Your father, on the other hand, was the better speaker and had an unusual gift for communicating, as reported by his contemporary, Manes Sperber. He was less of a writer. Why did he not learn to write better? He was always hard-working. He also did not dictate, which would have been better for him. He had no one to take dictation. For a long time he did not even have a typewriter. Many Individual Psychologists deplore the fact that your father did not present his thoughts in a more structured form and did not employ firm concepts. Yes, that is too bad. Others had done this for him. Heinz and Rowena Ansbacher, for example. Why did you not do that? I was a physicist and a mathematician. After I had come to the United States, studied medicine, and taken a degree in psychology, I entered the army. I had no time for that. During World War I your father was a neurologist in the Austrian army. Even as late as 1916 he showed little sympathy for deserters and so-called war-neurotics. How is that possible for a convinced anti-monarchist, republican, and socialist? From the very beginning, my father was an anti-militarist. He had nothing against those who did not want to fight. He thought that when someone shirks his duty, another has to take over. He was against shirkers. After the war your father denounced the misuse during the war of the concept of social feeling. He did that in a study on mass psychology entitled: "Die andere Seite" (1919) [The Other Side].

Subsequently, the Nazis then also misused that concept. Perhaps the concept ofd social feeling is easy to misuse. The English expression "social interest" seems more appropriate. "Sozialgefühl," "soziales Interesse" I find that also better. After Adler had begun to create his original ideas, he was practically cast out by Freud. Later, around 1925, Adler also felt himself betrayed by some of his own supporters, especially by the Marxist Individual Psychologists Manes Sperber, Alice Rühle-Gerstel, and Otto Rühle. He was said to have reacted like Freud. Oh, no. He had always only objected to Individual Psychology following a political line, which would not have been broad enough, and would have led to one-sidedness. Sperber later admitted his mistake. Sperber criticized your father for having concentrated his research too greatly on the individual and the family, and for having neglected the connection between individual problems and the framework of economic and social demands. My father had also looked into social backgrounds. Everyone had done that ! Do not some Individual Psychologists place too much emphasis even today on the decision-making possibilities of the individual, and neglect the framework of social demands? The concept of Individual Psychology leads to misunderstandings. It should intimate that every individual is to be regarded as an indivisible whole, and that it becomes a matter of establishing what this individual has made of his role in society. Does that not also include changing and improving society? Of course. The individual should assist in advancing society as a whole and to help in its further development. That is the purpose of Individual Psychological treatment. It seeks to make the individual cooperative in order to bring about social progress. Is it possible that this goal is often forgotten today? Yes, I am convinced of that. But, that has nothing to do with my father. These may well be the people who follow my father's pupil, Rudolf Dreikurs. Dreikurs places the emphasis on education. This was also true for your father, especially after his experiences in the First World War. The difference is as follows: My father wanted to educate the teachers so that they would transmit the correct attitude to the children. Dreikurs wanted to educate the parents. I consider that impossible. Particularly in the United States. The parents cannot be reached. Why is it not possible to begin at both ends? It is because the parents come from so many different backgrounds. Education today is almost no longer possible. I don't know what can be done about that. Do you think that the anti-authoritarian education wave of the sixties and seventies, so badly misunderstood by many parents, has something to do with that? Much! Did it produce pampered children, who consequently are badly burdened and who have no self-confidence? The children actually pamper themselves in that they say: "I have a right to make of myself whatever I wish, and, in fact, right now." The parents for their part neglect their children. When this also pertains to active children, the step toward criminality then is not long. Is the concept "pampered child" possibly one of those pertaining to Individual Psychology that is frequently misunderstood? Yes. "To pamper" means to love the child, to indulge. That has to be done when the child is young. However, the child must also be raised to become independent. The problem does not lie in that the parents pamper their children; the child pampers himself. How can a child pamper himself if the parents don't go along? The child pampers himself when he insists on having his own way. He can have his way only if the parents give in to him. Whether the parents say yes or no, in the end there is always a struggle. If such a child does not get his way, he is either depressed or he follows a wrong course. Children will pamper themselves even when they are not pampered by their parents. How would your father assess the current drug problem? I have asked myself that question also. At this moment I am in the process of studying the lectures he had presented to physicians and to other groups. Can't you deduce this? Oh, yes. I know what he thought about drugs. He saw them as means for escape, for running away from a reality that cannot be borne. But that is the trouble. There are so many unbearable realities today. In this case social conditions again play a part. How can one then explain how the drug situation has become such an insolvable problem in a country like Switzerland, where unemployment, until a few years ago, was low, and social inequality far pronounced than in the United States? I believe the younger generation everywhere has doubts about attaining what their fathers had achieved. They do not believe that they can become as successful and wealthy as their parents. Which may well be correct, given our times. Yes, recognizing this is almost unbearable. For that reason they create for themselves with drugs an easily attainable fantasy world. Added to this is a lost Utopia: the hope under socialism for a just distribution of wealth. Today, everything seems to run in the opposite direction. Yes, the trouble is that the ideals are missing. The new generation also has little interest in politics. You see the world today from a perspective of a person who has lived for the past sixty years in New York. Can you still recall the year when you immigrated? I received my degree in physics in 1935. We immigrated in the fall. My mother was arrested just before that. Why was that? She had volunteered for the "Red Help," a communist aid organization. My father was able to get her out of jail. He had to promise, however, that he would take her out of Austria. That was the reason for our immigration to the United States. At that time Stalin had already isolated Trotzky, and had emasculated the left and right wings of the party. What was your mother's stand on that? My mother was not a Stalinist. She sympathized with the Fourth Internationale. We knew Leon Trotzky. A family with socialist ideals immigrated to the United States, a capitalistic country. How did your family rationalize that? Austria at that time was just as capitalistic. Individual Psychology is one the three great schools of psychology in this century. In contrast to Freud's psychoanalysis and the arch-typical theories of C.G. Jung, it is the smallest school in Europe. Is this also true for the United States? In certain regards, yes. How come? Individual Psychology requires people to behave socially. Freud's analysis does not. I don't know enough about Jung's psychology. It is very highly regarded by artists. Your father seemed to have anticipated future developments. He said the following about the significance of Individual Psychology: –"It will gain many followers who will be free of prejudice. Many more people, however, will hardly know the name of the founder...." – "It will be understood by some, but the number of those who will misunderstand it will be far greater...." – "Because it is so clear, many will find it simplistic. Those who understand it will recognize its difficulty ...." In fact, there are many psychologists in Europe who are of the opinion that Individual Psychology is something for simple folk. Is this not a somewhat sad development? (Hesitatingly) I believe that it will be difficult in the near future, particularly in the USA, where the Republicans just won a great victory, and liberalism is down. It will be necessary to remain in opposition. To this must be added that important elements of your father's theories were absorbed by Sigmund Freud's followers. These appear under different designations, for example, as applied in Humanist Psychology. Naturally. Is it possible that in an age of manifold competing forms of therapy, old wisdom can only be introduced to the "therapy consumer" packaged in new ways? (Laughs). It happens frequently when I listen to lectures or addresses to hear statements of my father without his being named as the originator of what is being presented. For example, Professor Walter Bonime of the New York Medical School once declared that the kernel of depression is anger. My father discovered that already in 1920. When I asked Walter Bonime from where he took that statement he answered: "From Karen Horney." With the background of a cost explosion in the health field, and given the innumerable forms of therapy, the insurance companies in this country increasingly pose cost-effective questions. Payments are to be made only when a method being applied proved to be effective for the particular ailment being treated. What do you think of this kind of quality control? Individual Psychology maintains that a cure can only be effective depending on the patient. The therapist should not boast of having cured the client. The latter cures himself in a dialogue with the therapist. If he fails to do so, he has reasons not to change himself. That has little to do with the therapist. Lately there has been much talk here about cognitive behavior therapy which has best been documented as effective in cases of phobias and panic attacks. In such surveys social phobias are included. If, for example, someone barely escaped drowning and subsequently fears going into deep water, it can hardly be called a genuine phobia. Such problems are easily cured. If those are included in surveys, then the results will show a high percentage of successful cures. What are your views on hypnotherapy? An absolutely unscientific procedure! The patient leaves the responsibility to the hypnotist and does not change in the least. How about hypnosis to abate fear? Even fear has a reason which has to be established. The reason might be found in childhood. However, that takes more time. At the moment less time consuming therapies are popular, for cost reasons. The idea of short-lasting therapies is nonsense because attention must be paid to the individual. In some cases three therapy sessions will arrive at results; in other cases it takes years. You have been active as a psychiatrist and psychotherapist for about fifty years. What advice would you give to younger colleagues, based on your vast experience? What, for example, makes for a good psychotherapist? That he become a friend to his clients. Is that a basic position? Can it be learned? A person who does not like people should not become a psychotherapist. What are the driving, the relieving forces in the therapeutic process? What causes a change? An understanding of how one has arrived at one's mistaken beliefs, beginning with childhood. An understanding of the purpose, the goals of one's own behavior. In English we speak of "goal-directedness." This has to be worked out together with the client. He will not find it alone, else he would have discovered it long ago.

It seems to me that what is difficult in this is not to rush ahead of the client, but to leave the tempo up to him. That can be learned. In the New York Adler Institute we have a one-way mirror. The dialogue between the therapist and client takes place in that room. Our students observe in the adjacent room and follow the dialogue, of course, only with the client's consent. Both the client and therapist forget the presence of the observers in the course of their talk. Are there clients who cannot be subjected to therapy? Who says that there are such people? Then the only question is one of ability and time? No, it is a question of willingness. There are many advantages to a person for not being willing to change. Otherwise there would be no reason for behaving like he does. This means that one has to recognize the many advantages to changing. Often this is successful. What is your view of psychotherapy for psychotics? I treat psychotics. Today greater weight is given to the genetic aspects in psychoses. Also, treatment depends to a considerable extent on medication. The purpose of medication is to make the client listen, and to lead him toward cooperation. Medication can and should be used. However, it cannot achieve more than that. Do you treat schizophrenics? If yes, successfully? Yes. If they stay. Does this last many years? Yes. Are you successful in curing them? What does curing mean? Can such people manage their lives more easily? They can work, marry, have children, but they do look a little different. Even after therapy? Yes. Your father was an optimistic therapist. Would he be the same given the background of today's world? One has to think historically. How long have people lived on this earth? What if it were to take another thousand years for people to become more sensible? I hope, of course, that it will not take that long. You have such hopes in spite of the all the tendencies in the opposite direction, despite the striving for superiority and power, despite crass nationalism, despite the current deconstruction of social gains? Are humans actually not social beings? Are Adlerians, are you, fighting a losing battle? The developments are leading to a catastrophe. Then everything will be different; unless social feeling will be victorious first. Many are warning that it is already five minutes before midnight. They have been saying that for a long time. You believe, therefore, that social feeling will win out, despite the current tendencies in world politics. There are also positive political signs. For example, the political developments in South Africa. And the dissolution of the former Soviet Bloc? The fact that the communist dictatorship has collapsed is genuine progress. The development, however, can go too far. You are ninety years old. Are you aware of your own finiteness? (Laughs) Of course. Is death the end of everything? Whatever I have achieved and done remains. (End of Interview) |

Back to Other Original Adlerians

Back to Other Original Adlerians

Back to Home Page:

Back to Home Page: